THE STRATEGIES OF DAVID

We have heard the stories of David and Goliath. David’s strategy was to aim at Goliath’s one point of weakness, the spot on the giant that wasn’t armored.

The American school system was such a Goliath, heavily armored in layers of bureaucracy that resisted the calls for change. An education reformer and former New York City teacher said it best: “The American education system is broken, failing too many children,” according to John Taylor Gatto. Impersonal bureaucracies and cookie-cutter approaches left far too many children behind, particularly in America’s largest cities.

The American school system was such a Goliath, heavily armored in layers of bureaucracy that resisted the calls for change. An education reformer and former New York City teacher said it best: “The American education system is broken, failing too many children,” according to John Taylor Gatto. Impersonal bureaucracies and cookie-cutter approaches left far too many children behind, particularly in America’s largest cities.

Gatto wrote that reform would take nothing less than “blowing up the system.” Fortunately, it didn’t come to that. It instead took the slingshots of passionate individuals driven with a singular purpose, “to provide educational opportunities for all children.” The proverbial stone in David’s sling was an idea so powerful that it built a nationwide network for educational change.

BIPARTISAN STRENGTH AND SINGULAR FOCUS

The Wisconsin Charter School Association represented every area of the state, every political faction and every network concerned with children and education. What gave this unfunded charter school movement strength at a time when there was no cash to buy political influence was simple: courage.

The sheer number of grandparents, parents, teachers, administrators, community groups and individuals together, all determined to put children’s lives first, made that difference. Our phone calling trees, faxes, and routine visits to state legislators’ offices made that difference. We didn’t need to be paid to do the right thing. It was simply the right thing to do!

Those of us in the charter school movement in the early 1990s raised our voices with such clarity of purpose and passion that lawmakers had no choice but to listen. We spoke with one voice and gave one message that was easy to understand: children in impossible educational systems deserved a way out.

Technology would create an opportunity to reach all legislators and leaders in a position to call for a vote on our legislation. The automatic fax dial-ups on our computers made hundreds, of supporters appear to be thousands of supporters, which then grew into tens of thousands of supporters overnight. The political muscle of the people (more specifically, parents and community leaders) was unwavering in the fight for the rights of children to have quality education.

The sincerity of parents who were fighting for the survival of their families could not be denied. No political need for power or control, no position of power or control, and no heavily funded union, association or political machine could stand up to the conviction of a family’s right to fight for its own survival. Education equates to survival for families whose children have fallen through the cracks of public schoolhouses.

State constitutions across this country guarantee every child’s “right to an education.” This political and legal argument became so powerful that it indeed swayed even the most reluctant politicians. Even those who dreaded the recourse from the union’s political action committee monies that would rain down against them, come election time.

And, as they say, “The rest is history.” Today, Wisconsin has well over thirty thousand students in public charter schools—many of them in my own backyard.

Senn Brown, a lobbyist of the school board association, confirmed the importance of the vote and the changes in education law, as he whispered in my ear the day of the vote, “Terri, look what you have done! The charter school law is one of the most significant public school reforms in Wisconsin’s history.”

I had the honor of leading and being a part of one of the most important movements in the history of the state of Wisconsin—a civil rights movement to many, and my core conviction as a citizen leader. We had done it! Zero dollars to lobby politicians, and the results were priceless; we would touch countless families and future generations, even though we would never meet.

To continue reading this chapter, get your copy of “What Sex is a Republican in paperback or Kindle edition on Amazon.

About the Author:

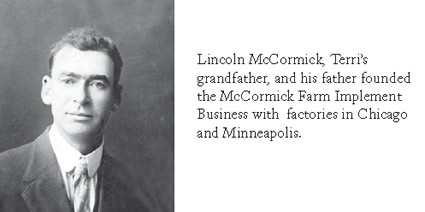

Terri McCormick is an author, policy expert, educator, and former state representative to the Wisconsin State Legislature. Today, she offers her expertise in public and government relations through McCormick Dawson CPG Ltd., a trusted consultancy of independent contractors.

Ms. McCormick serves as president and CEO of the company, drawing from more than two decades of professional experience, a strong educational foundation, a host of industry-related publications, and a multitude of accolades, awards and formal recognitions. Holding a Master of Arts in administrative leadership from Marian University, and a Bachelor of Science in political science and public administration from the University of Wisconsin, Ms. McCormick received both degrees with high honors.

“What Sex is a Republican?” is sold on Amazon in both the paperback edition as well as Kindle edition. Read reviews on Amazon here.

The source of resistance to change is human emotion. In the political environment, reaction and perception are reality.

The source of resistance to change is human emotion. In the political environment, reaction and perception are reality. Creative and innovative, Bill O’Brien was looking for outside-the-box ideas in providing a curriculum for his financially strapped school district. More important, he had a class in one of his middle schools that had a reputation for chasing good teachers out of the teaching profession.

Creative and innovative, Bill O’Brien was looking for outside-the-box ideas in providing a curriculum for his financially strapped school district. More important, he had a class in one of his middle schools that had a reputation for chasing good teachers out of the teaching profession. In today’s society of instantaneous communications via blogs and the Internet, we must all guard against journalists who are tempted to forego the following values and principles by way of self-interest and greed. According to the Society of Professional Journalists, the ethical standard of professionalism is to “seek truth and report it.

In today’s society of instantaneous communications via blogs and the Internet, we must all guard against journalists who are tempted to forego the following values and principles by way of self-interest and greed. According to the Society of Professional Journalists, the ethical standard of professionalism is to “seek truth and report it. I have been asked, “Why did you choose politics?”

I have been asked, “Why did you choose politics?”